Great Barrington Beginnings

W. E. B. Du Bois, Social Welfare Scholar and Civil Rights Activist Du Bois often started his story with, “I was born by a golden river and the shadow of two great hills, five years after the Emancipation of Proclamation” (Du Bois, 1920, p. 5). His family was among the few Black families in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. Like Wharton, he grew up without his father—a barber and laborer who left his mother when he was 2. By the time his mother died when he was 16 years old, he had already established himself as intellectually gifted and self-reliant, excelling in school and serving as a local correspondent and distributor for the New York Globe, a Black newspaper (See Figure 1.2).

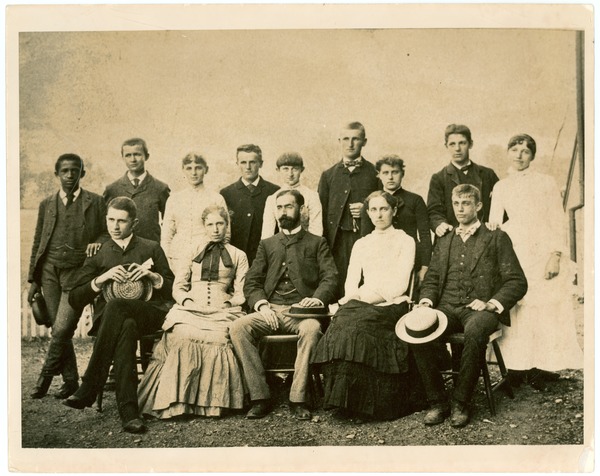

Du Bois poses with his high school class from Great Barrington in 1884. (Image courtesy of the UMass Amherst W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, 1803-1999.)

Pictured Above: Du Bois with Class of 1884 from Great Barrington High School. W. E. B. Du Bois, standing far left, was the class valedictorian at age 16.

Headed South

Like other bright boys growing up in Massachusetts, he dreamed of attending Harvard University. However, the racist systems of his day thwarted his youthful dreams and instead, local churches raised funds to send him to Nashville’s Fisk University, a historically Black university, in the segregated South.

Du Bois later earned a second bachelor’s degree from Harvard and a doctorate—the first issued by Harvard to a Black student—and enjoyed 2 years of study in Berlin with Europe’s leading sociologists. Du Bois loved his time in Europe, where he was intellectually challenged and treated like a man, not a Black man. “I was not less fanatically a Negro,” he explained 30 years later, “but ‘Negro’ meant a greater, broader sense of humanity and world-fellowship. I felt myself standing, not against the world, but simply against American narrowness and color prejudice” (Du Bois, 1920, p. 16).

At Harvard, on the other hand, Du Bois lived a segregated social life, gravitating to other Black students studying at nearby universities. Du Bois described this “voluntary segregation” as a defense against the dominant ideas about race and integration among Harvard’s White faculty and students. He described the years after coming back to the United States as “the days of disillusionment. After completing his PhD, he tried in vain to obtain employment as a teacher on the East Coast, eventually accepting a position at Wilberforce College in Ohio, a “colored church-school,” as a classics professor.

Du Bois poses with the Fisk University class of 1888. (Image courtesy of the UMass Amherst W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, 1803-1999.)

Du Bois' Family

W.E.B. & Nina Gomer Du Bois. (Image courtesy of the UMass Amherst W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, 1803-1999.)

Nina Gomer Du Bois grew up in Cedar Rapids, Iowa where her father was the head chef at Brown’s Hotel. She and Du Bois had two children, Burghardt who died in infancy when they lived in Atlanta, and Yolande who predeceased her father by two years. Nina and Yolande lived apart from WEB Du Bois for large stretches of time, although Nina did contribute to some of Du Bois’ civil rights activities.

Yolande’s father helped make a match with the Harlem Renaissance poet, Countee Cullen, even though he knew Cullen was gay. Cullen and Yolande married in 1928 in what was the social event of the year for the Black elite, with some 3,000 people crowding into the Harlem church.

Yolande divorced him shortly after and remarried, giving birth to Du Bois William, Du Bois’ only grandchild. Du Bois William eventually married Arthur McFarlane, Sr. and gave birth to Arthur McFarlane II, Du Bois’ first great grandson in 1957.

On the occasion of his 90th birthday, WEB Du Bois gave a speech directed at his great grandson who, years later, became a friend and partner to The Ward. Nina Gomer died in 1950 and WEB Du Bois married Shirley Graham, an American-Ghanaian writer and activist; her son, David Graham, took Du Bois’ name.

Atlanta University

After completing his study of the Seventh Ward, Du Bois received no faculty offers from White institutions in the North and accepted a position at Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta).

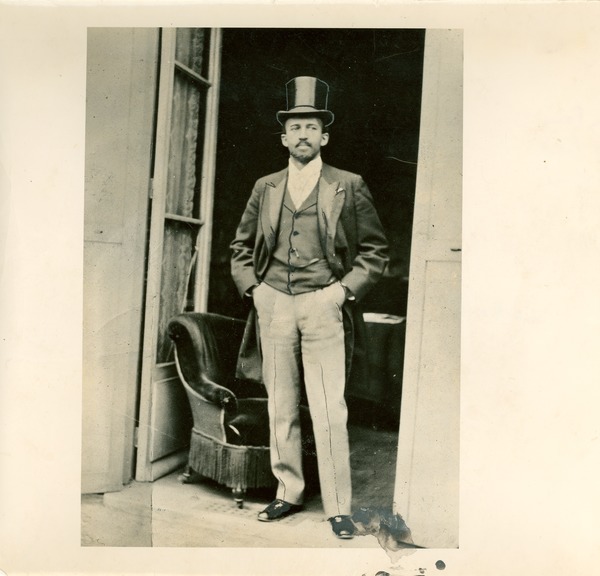

Du Bois at the Paris International Exposition, 1900. (Image courtesy of the UMass Amherst W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, 1803-1999.)

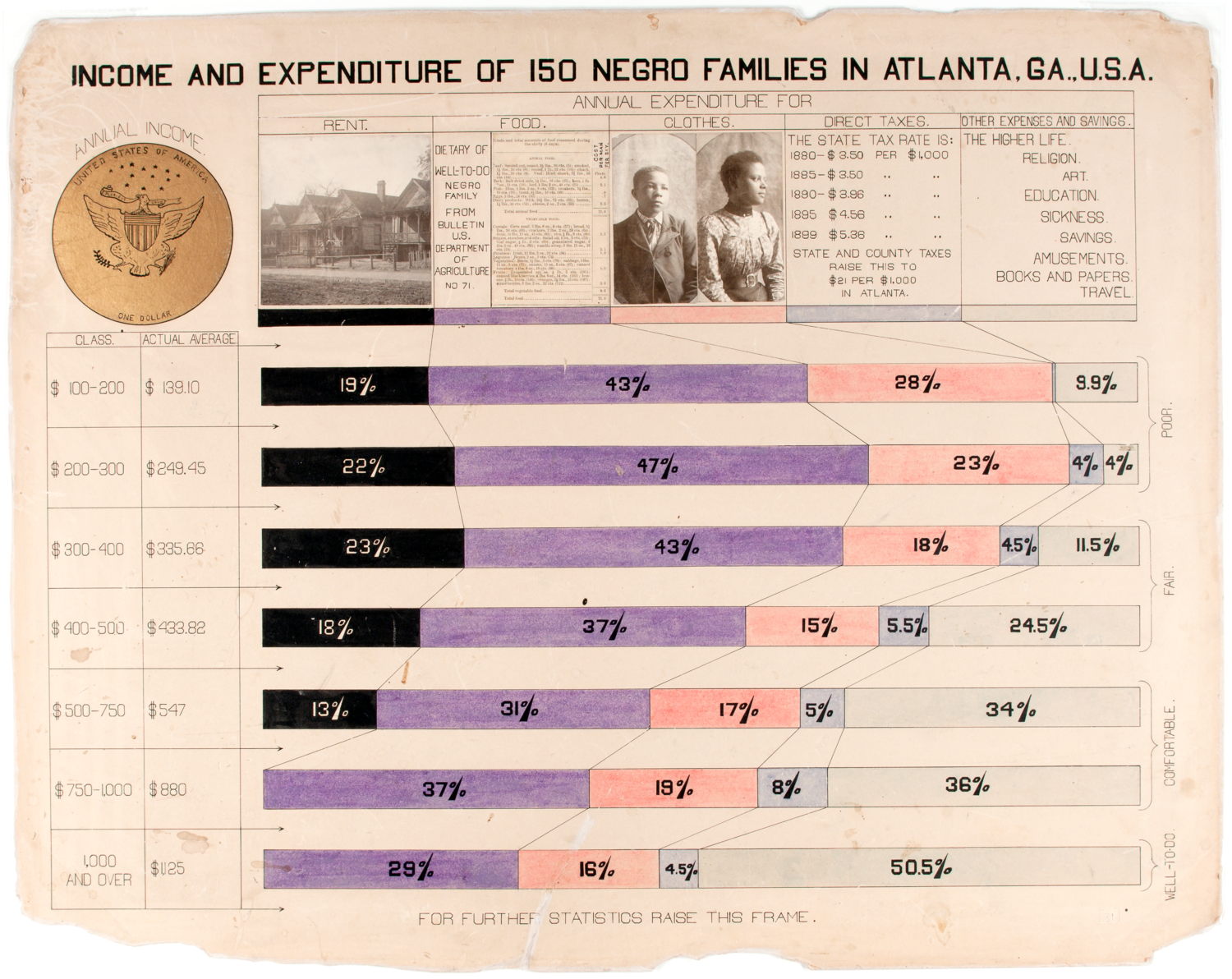

For over a decade, he led research about African Americans and established the highly influential Du Bois-Atlanta School of Sociology at Atlanta University. He organized a set of data visualizations for the 1900 Paris Exhibition aimed at documenting the humanity, agency, and heterogeneity of Black Americans, themes he explored in The Philadelphia Negro.

From Atlanta, he wrote the eloquent set of essays published in 1903 as The Souls of Black Folk in which he described his early experiences with racial prejudice, pain of losing his first-born son, and intellectual battle with Booker T. Washington. Du Bois also wrote about the lynching of Sam Hose in Georgia and called for national anti-lynching laws for national magazines, marking his disillusionment with academia that led him to join the staff of the NAACP.

Infographic from W. E. B. Du Bois’ Hand-Drawn Infographics of African-American Life (1900).

One could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved; and secondly, there was no such definite demand for scientific work of the sort that I was doing.

W.E.B. Du Bois, Dusk to Dawn (1940)

NAACP and The Crisis

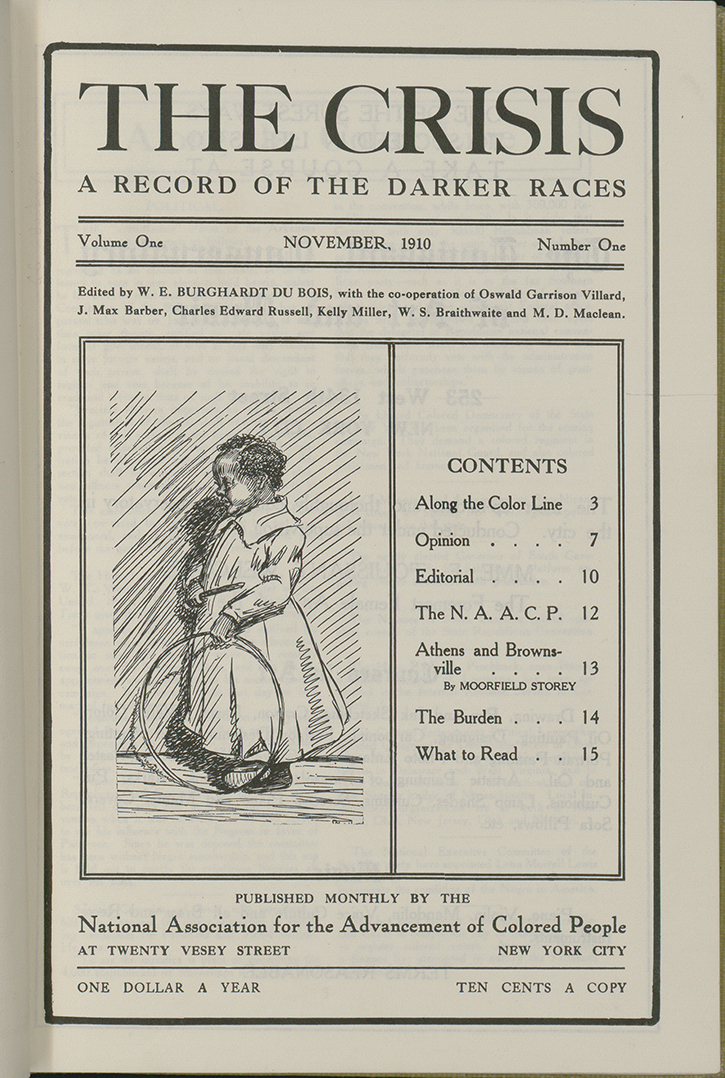

The lack of resources available to Du Bois at Atlanta University, in part a product of his intellectual feud with Booker T. Washington, who had great influence over White philanthropic funding, led Du Bois to resign from Atlanta University in 1909 and accept a position with the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to serve as the founding editor for The Crisis.

In launching The Crisis in 1910, Du Bois explained the publication would “set forth those facts and arguments which show the danger of race prejudice.” His goals were the same as with his academic scholarship, including The Philadelphia Negro, but now he had a much larger audience. This included “children of the sun” to whom he dedicated the monthly Brownies Book, “designed for all children, but especially for ours.”

Cover for the first issue of The Crisis from November 1910.

International Figure

On October 14, 1931, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote a letter to Albert Einstein inviting him to contribute a brief statement on the fight for freedom for The Crisis. Eistein sent the statement written in German and entitled, “To the American Negro.” Du Bois translated it from German to English.

To the American Negro

It seems to be a universal fact that minorities, especially when their individuals are recognizable because of physical differences, are treated by majorities among whom they live as an inferior class. The tragic part of such a fate, however, lies not only in the automatically realized disadvantage suffered by these minorities in economic and social relations, but also in the fact that those who meet such treatment themselves for the most part acquiesce in the prejudiced estimate because of the suggestive influence of the majority, and come to regard people like themselves as inferior.

This second and more important aspect of the evil can be met through closer union and conscious educational enlightenment among the minority, and so emancipation of the soul of the minority can be attained. The determined effort of the American Negroes in this direction deserves every recognition and assistance.

- Albert Einstein

W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collection and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

Capitalism cannot reform itself; it is doomed to self-destruction. No universal selfishness can bring social good to all. Communism—the effort to give all men what they need and to ask of each the best they can contribute—this is the only way of human life.

W.E.B. Du Bois, upon joining the Communist Party at age 93

Self-Exhile to Ghana

Du Bois’ career took him to Germany, Britain, the Soviet Union, China, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Senegal, and several other countries. In 1961, Du Bois joined the communist party and left the United States for Ghana. He became a citizen of Ghana in 1963.

Du Bois and his second wife, Shirley Graham. (Image courtesy of the UMass Amherst W.E.B. Du Bois Papers, 1803-1999.) University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries

The U.S. Post Office issued a 32-cent W.E.B. Du Bois stamp on February 3, 1990.

Before leaving the United States for Ghana, Du Bois joined the communist party. In May of 1961, President Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of Ghana, invited Dr. Du Bois “to pass the evening of his life” in Ghana and to devote his remaining years to compiling an Encyclopaedia Africana.

Nkrumah met Du Bois earlier in his career and recognized him as a father figure and a friend. He hoped that Du Bois’ influence would help liberate Africa from colonial rule. Du Bois received the honor and respect in Ghana that was denied him in his country of birth. Du Bois became a Ghanian citizen on February 25, 1963.

Perspectives

Du Bois and Nkrumah's Evolving Relationship

On August 27, 1963, on the eve of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Du Bois died at 95 years old. He is buried in Ghana as “a great son of Africa.” Read his obituary in the New York Times. Since Du Bois’ death, his legacy has been honored by several institutions including the United States Postal Service.

In Ghana, the W.E.B. Du Bois Memorial Centre for Pan African Culture was established in 1985. The W.E.B. Du Bois Museum Foundation is currently working to extend Du Bois’ legacy in the United States and Ghana. Watch this short video to learn more.

The U.S. Post Office issued a 29-cent W.E.B. Du Bois stamp on January 21, 1992.

Additional Learning

W.E.B Du Bois, Dusk of Dawn, 1940/1970 with foreword by Martin Luther KingW.E.B. Du Bois, Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil, 1920W.E.B. Du Bois, A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from Its First Century: The Autobiography of W.E.B. Du Bois, 1968/2003Shirley Graham Du Bois, His Day is Marching On: A Memoir of W.E.B. Du Bois, 1971Shirley Graham Du Bois, DuBois: A Pictorial Biography, 1979David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography 1868-1963, 2009David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919-1963, 2001Aldon Morris, The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. and the Birth of Modern Sociology, 2017Boddie and Hillier (2022), The Making and Remaking of The Philadelphia Negro, Digital Humanities Quarterly, 16(2)