Philanthropist Susan Wharton

As a board member of the College Settlement Association, Susan Wharton was responsible for enlisting the support of the University of Pennsylvania and bringing Du Bois to Philadelphia to investigate the Seventh Ward. She lived at 910 Clinton Street, a block from Pennsylvania Hospital.

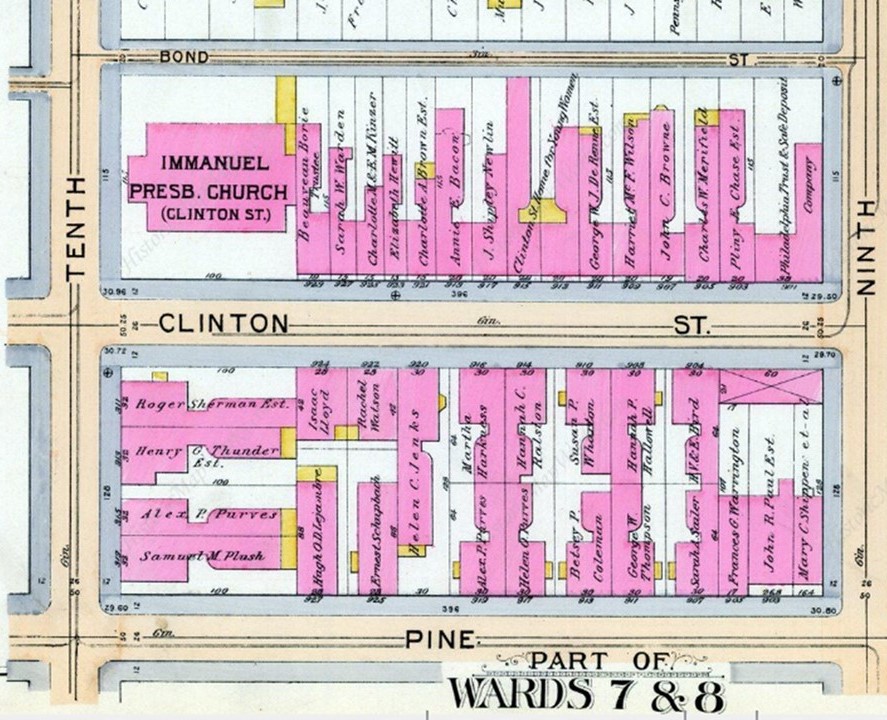

The 1896 Bromley Fire Insurance Map shows the names of property owners, including Susan Wharton who owned 910 Clinton Street.

Pictured Above: Du Bois with Class of 1884 from Great Barrington High School. W. E. B. Du Bois, standing far left, was the class valedictorian at age 16. Credit: W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

Born to an Elite Quaker Family

Susan Parrish Wharton was born in Philadelphia in 1852 to a wealthy Quaker family. In addition to the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, her uncle, industrialist Joseph Wharton, helped establish Bethlehem Steel and Swarthmore College. Her maternal grandfather, the eminent physician Joseph Parrish, was a leader in the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery and his house was a stop on the underground railroad.

Being from Philadelphia, she attended nearby Swarthmore College like many of her family members. Many other women involved in the Settlement House Movement attended all-women’s schools: Smith, Vassar, Wellesley, and Bryn Mawr (Rousmaniere, 1970). Swarthmore was coeducational from the start but remained all white until the 1940s.

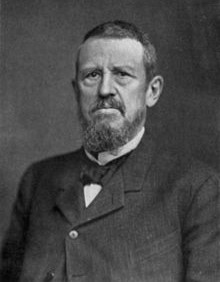

Joseph P. Wharton, Susan’s uncle.

House on Clinton Street

Susan Wharton lived with her mother, Susanna, at 910 Clinton Street, a stately brick row house in Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward.

Wharton’s home at 910 Clinton Street. (Image from Google StreetView.)

The household was sustained by the wealth of Susan’s father, Rodman, who died when Susan was young, and extended family. Wharton lived just a block from Pennsylvania Hospital, the nation’s first hospital, and five blocks from Independence Hall. The other houses on the block were also owned and occupied by single White families headed by lawyers, merchants, engineers, and people of independent means.

The block was also home to many live-in servants—referred to as mistresses, cooks, chambermaids, and housekeepers—likely the only Black residents on the block. This is where Wharton gathered Black and white community leaders to discuss the need for a study of the Black residents of the Seventh Ward.

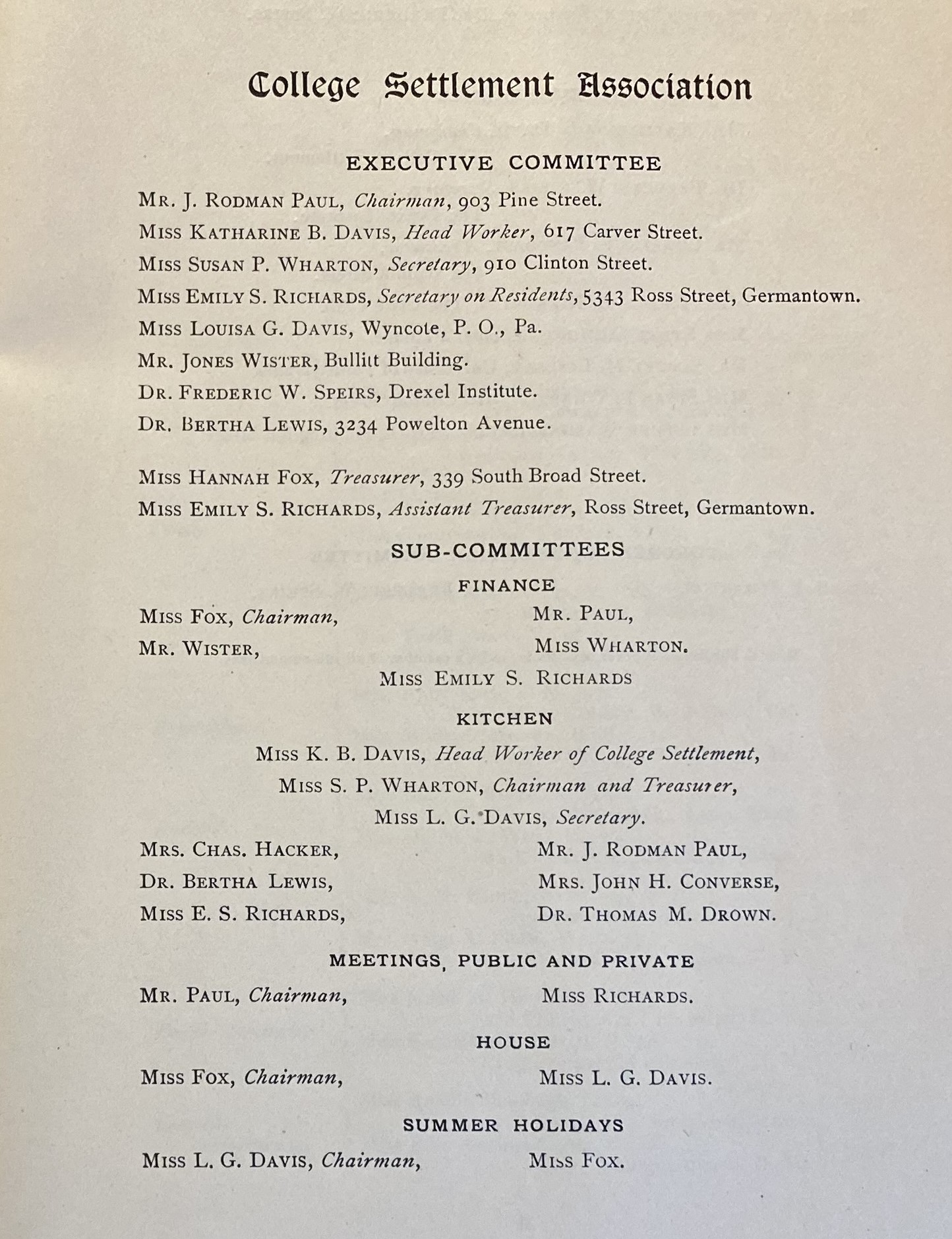

Leader of College Settlement Association

Like her grandparents, Wharton committed her time and resources to helping Black people, especially those living in poverty in Philadelphia. Philadelphia’ College Settlement Association grew out of the St. Mary Street Colored Mission Sabbath School, established in 1857 by philanthropist and abolitionist George Stuart, and included a nursery, kindergarten, and playground. Wharton added the St. Mary Street Library in 1884, eventually incorporating carpentry and cooking classes for Black children.

With her cousins, Hannah Fox and Helen Parrish, Wharton formally associated the St. Mary Street Library with the larger college settlement movement in 1892, renaming the organization the College Settlement of Philadelphia, referred to simply as “the Settlement.” Wharton took on numerous roles and contributed financially to the Settlement until it moved to Christian Street in 1898.

Fifth Annual Report, College Settlement Association, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Whittier and Wharton Center

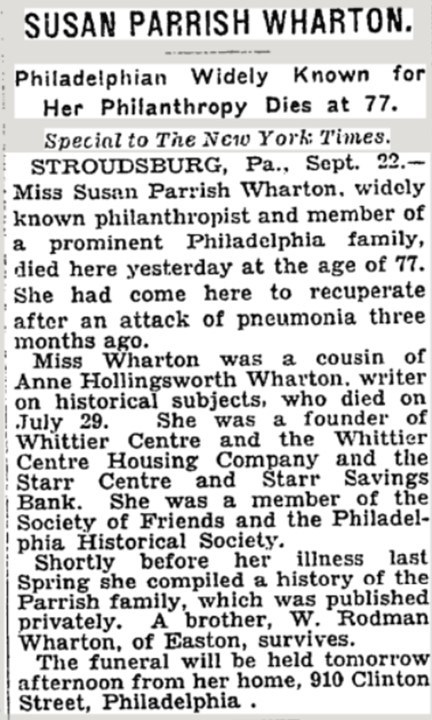

The New York Times published Susan Wharton’s obituary in September 1928.

When the Settlement moved to Christian Street, Wharton stayed put at 7th and Lombard Streets to help lead the Starr Center, including a library, bank, coal club, lunch program, and ever-expanding health services. In 1912, she helped found the Whittier Center, focused on the health and housing needs of the Black community in the same area.

The Whittier Center eventually moved to North Philadelphia, following the migration of Black Philadelphians out of the Seventh Ward, and was renamed the Wharton Center after her death. The Whittier Center developed deep connections with the surrounding Black communities and had a board composed of Black and white leaders.

These cross-racial relationships and community trust were critical factors in the organization’s success working with the Henry Phipps Institute to mitigate racial disparities in tuberculosis.