Overview of the Curriculum

Our goal from the start was to develop curriculum, especially for Philadelphia’s required high school African American History course. Most of the elements of our project--the documentary, interactive mapping, board game, and walking tour--were designed with students in mind. Beyond developing materials, ourselves, we are excited to be partnering with teachers and students to create curriculum.

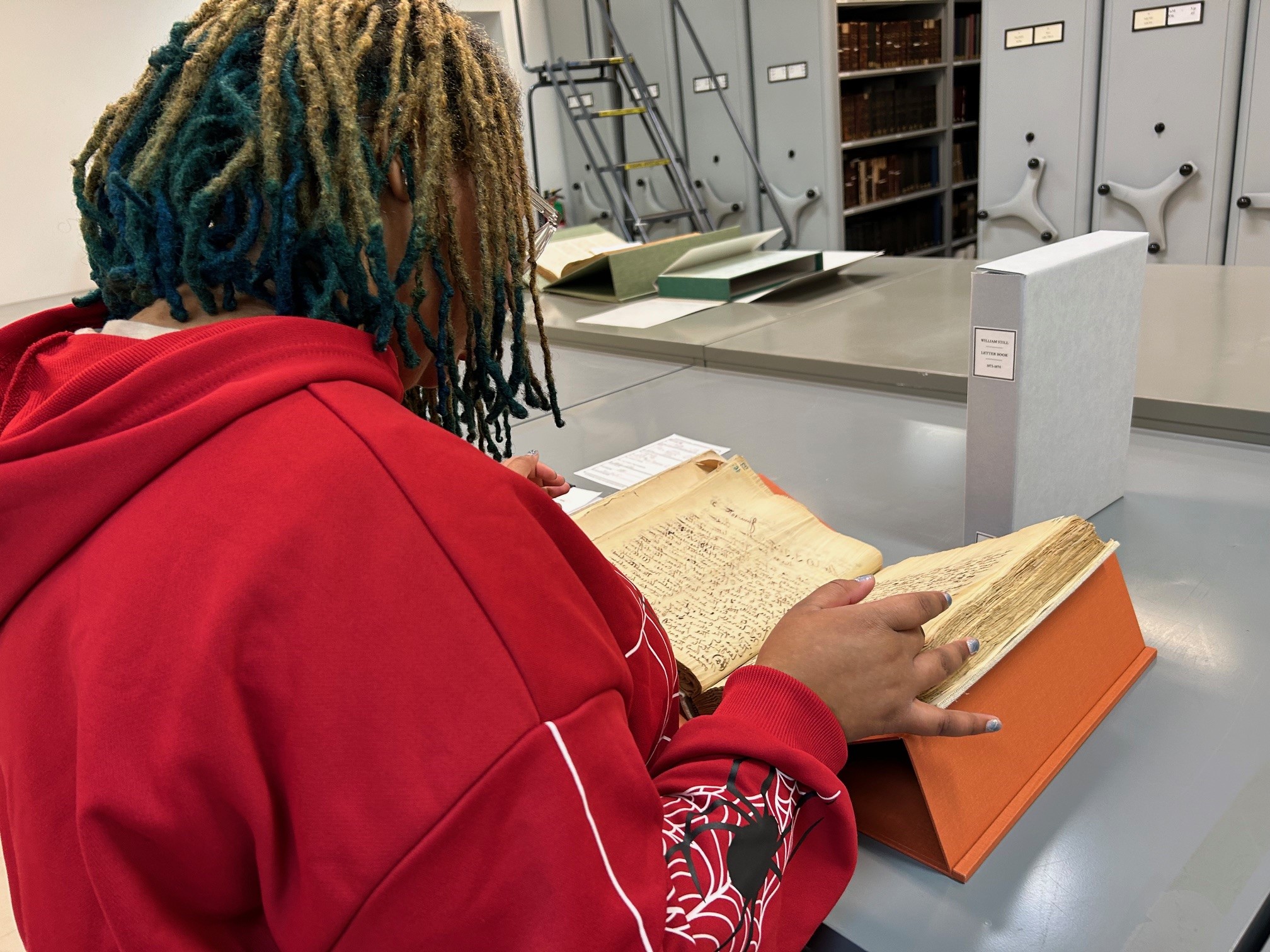

Penn students explore primary sources at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Primary Source Worksheet

Philadelphia maintains amazing archives, full of rich primary sources. Through our primary source exploration, students closely examine copies of census records, historical newspaper articles, and photographs.

Students then complete a document analysis worksheet, adapted from the National Archives , answering questions about the intended audience, creator, the purpose for the document, whether the creator had first-hand knowledge, was a neutral party, and whether the document was intended for public or private use.

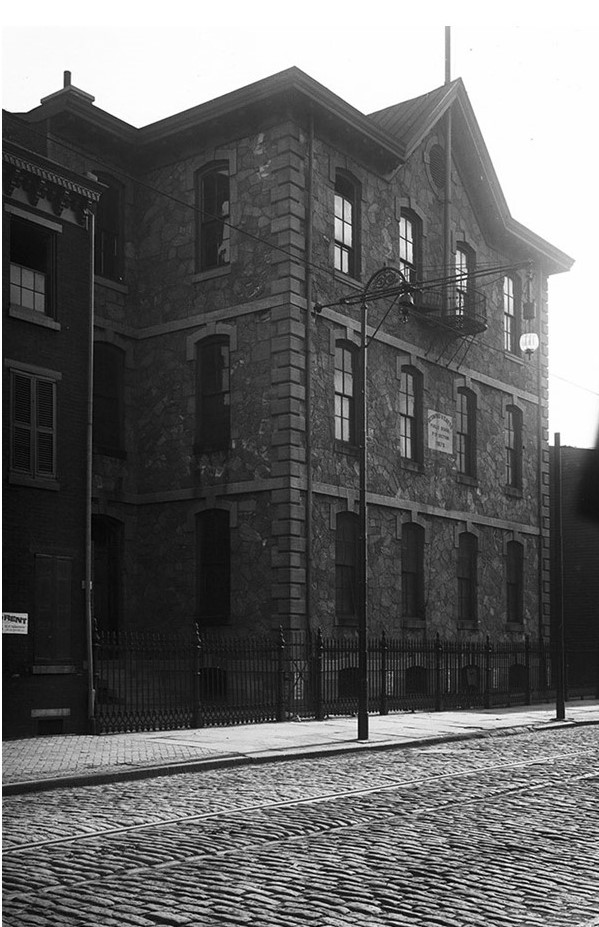

The Octavius Catto School was named for the martyred civil rights hero, Octavius V. Catto who was shot and killed on election day in 1871.

Interactive Mapping

Amy Hillier’s background in geographic information systems (GIS) has led her to integrate mapping exercises about the Seventh Ward in schools.

These exercises have changed over time, as the software and functionality of the Seventh Ward GIS has changed. Students explore where boarders/lodgers and servants lived as a proxy for household income and the patterns in race, place of birth, and occupation of residents.

Students are also introduced to the Philadelphia Geohistory Network map viewer where they can explore dozens of different historical maps and PhillyHistory.com, home to tens of thousands of scanned historical images.

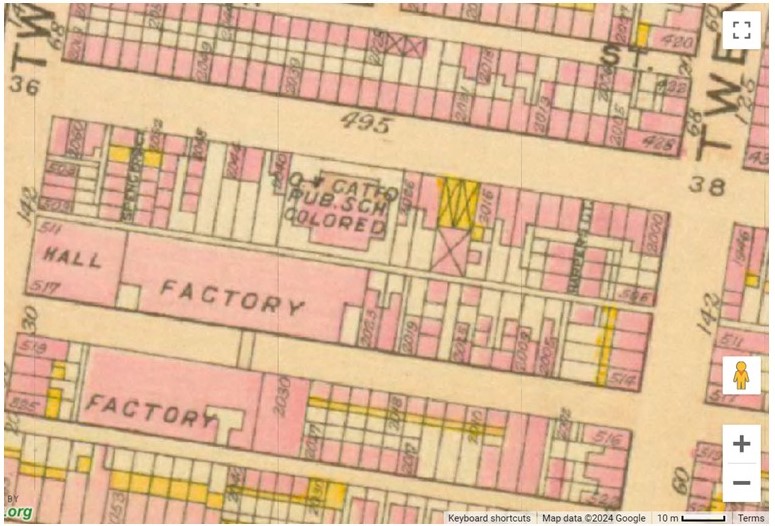

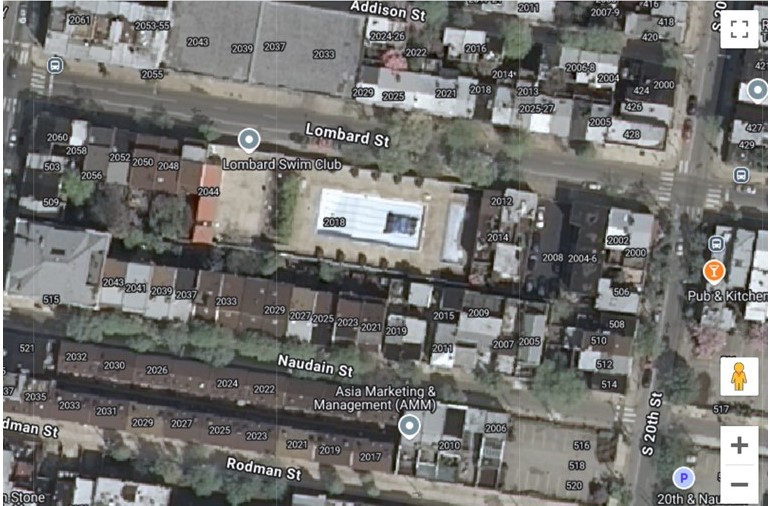

One example students consider is the Octavius V. Catto Public School for Colored students, built in 1879 on Lombard Street beside the Kennebec Mills woolen yarn factory. The school was led by principal Caroline LeCount who was engaged to O.V. Catto when he was murdered on election day in 1871 while trying to help Black male residents vote.

The school was closed and demolished by 1940, and in 1961, became home to the members-only Lombard Swim Club.

Using online interactive GIS maps, students can compare historical and contemporary buildings.

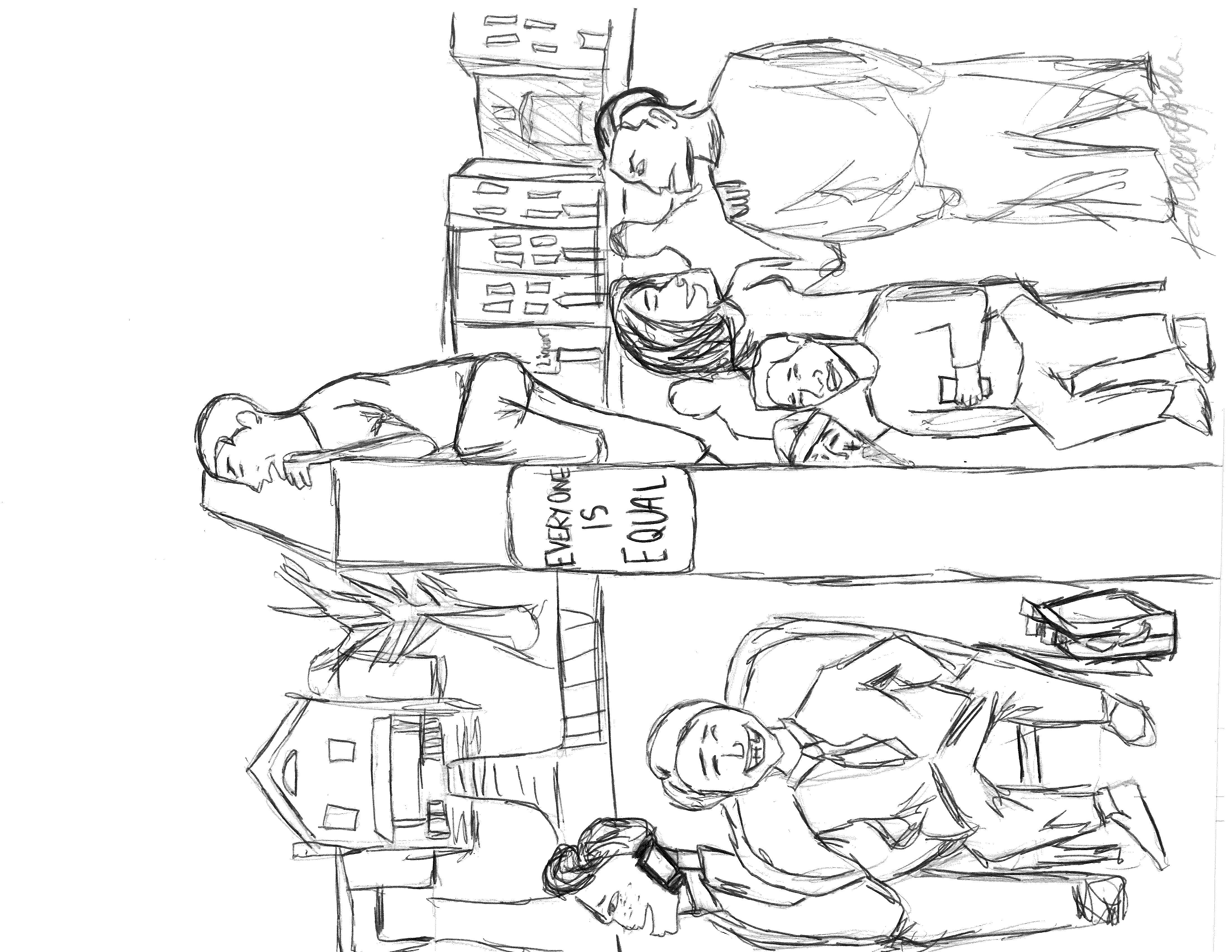

Silent Conversation

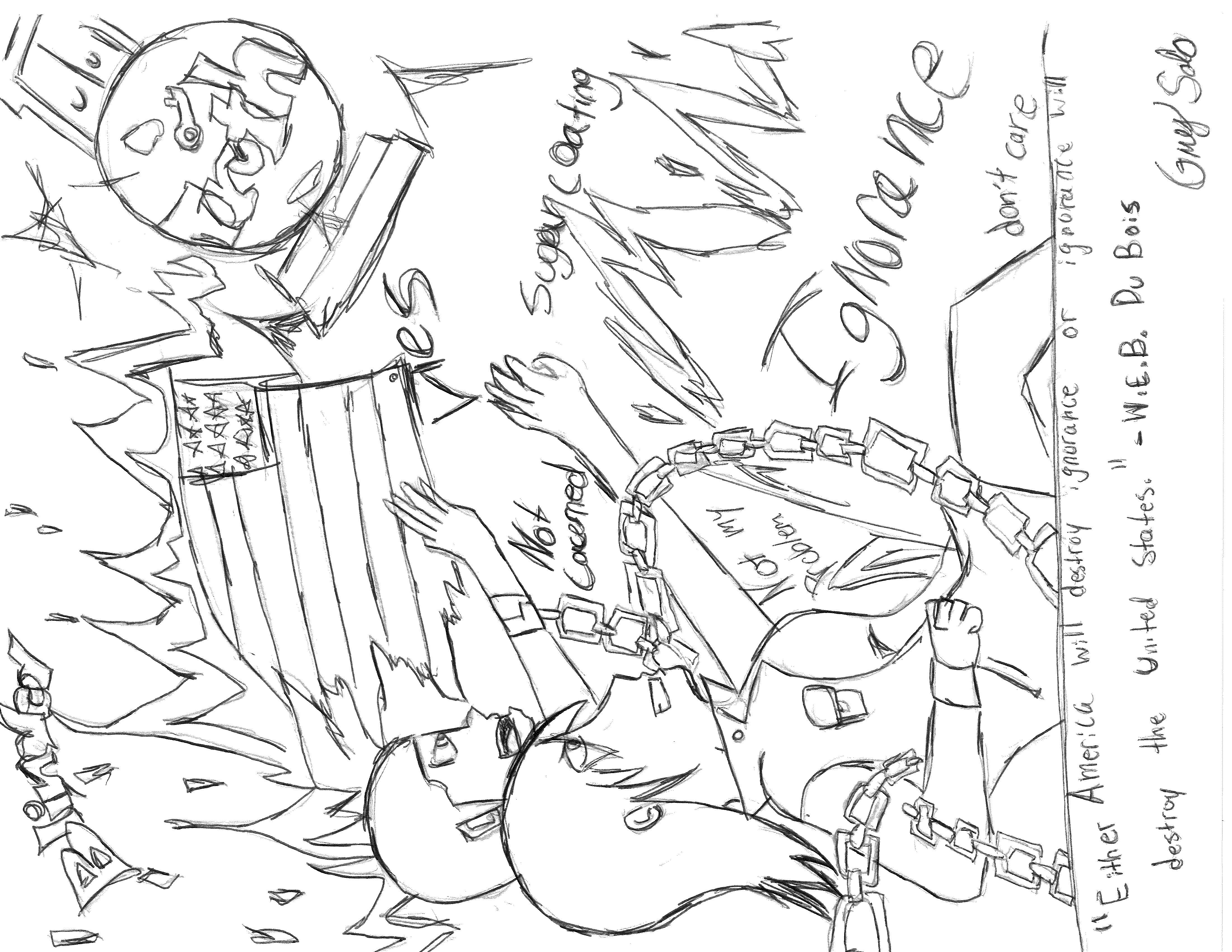

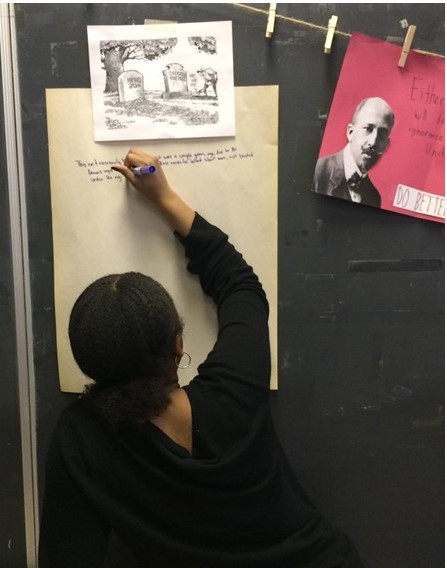

Students from Masterman High School participate in a “silent conversation,” writing comments about visual prompts such as political cartoons.

The silent conversation activity encouraged students to reflect on historical and contemporary issues by engaging with visual and textual prompts. Through written commentary and peer interaction, students connected their perspectives to Du Bois’ era, fostering critical thinking and culminating in thoughtful discussions that bridged history with modern-day concerns.

When working with Masterman High School, we showed our documentary, “A Legacy of Courage,” on the first day, highlighting Dr. Tukufu Zuberi’s insistence that, like Du Bois, every generation has to identify the issues of its day. We then asked students to brainstorm the main issues of the day that they cared about and make connections between those and the issues Du Bois faced.

These topics then served as the basis of a “silent conversation” on the fifth and final day, with students moving silently from one image or quote posted on the wall to another, adding comments based on the original prompt or the comments of their classmates. We used political cartoons (including some from Samuel Joyner), data visualizations, quotes from Du Bois, and photographs as prompts. After the students viewed and commented on all of the posts, we chose one or two as the focus of a (not silent) conversation.

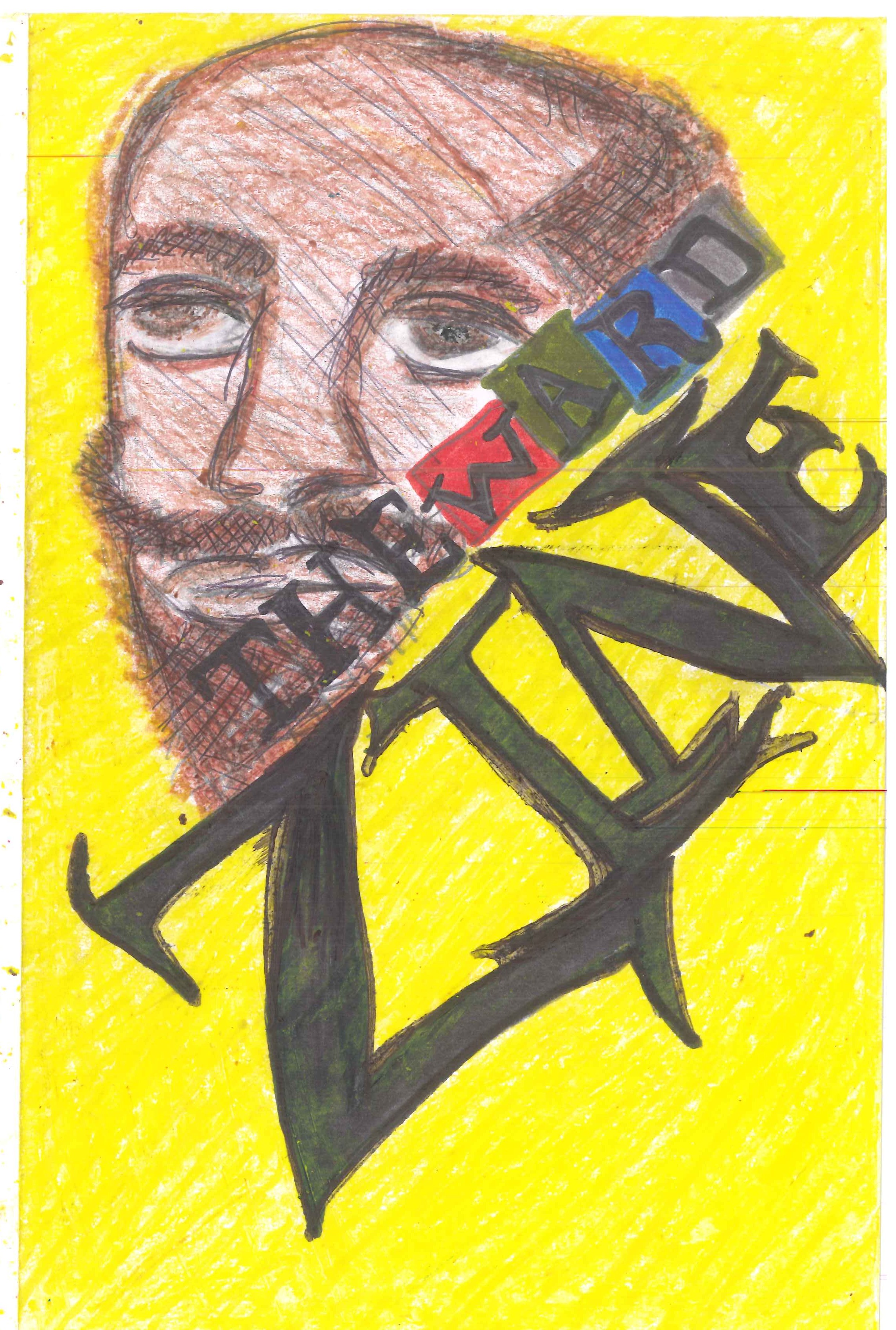

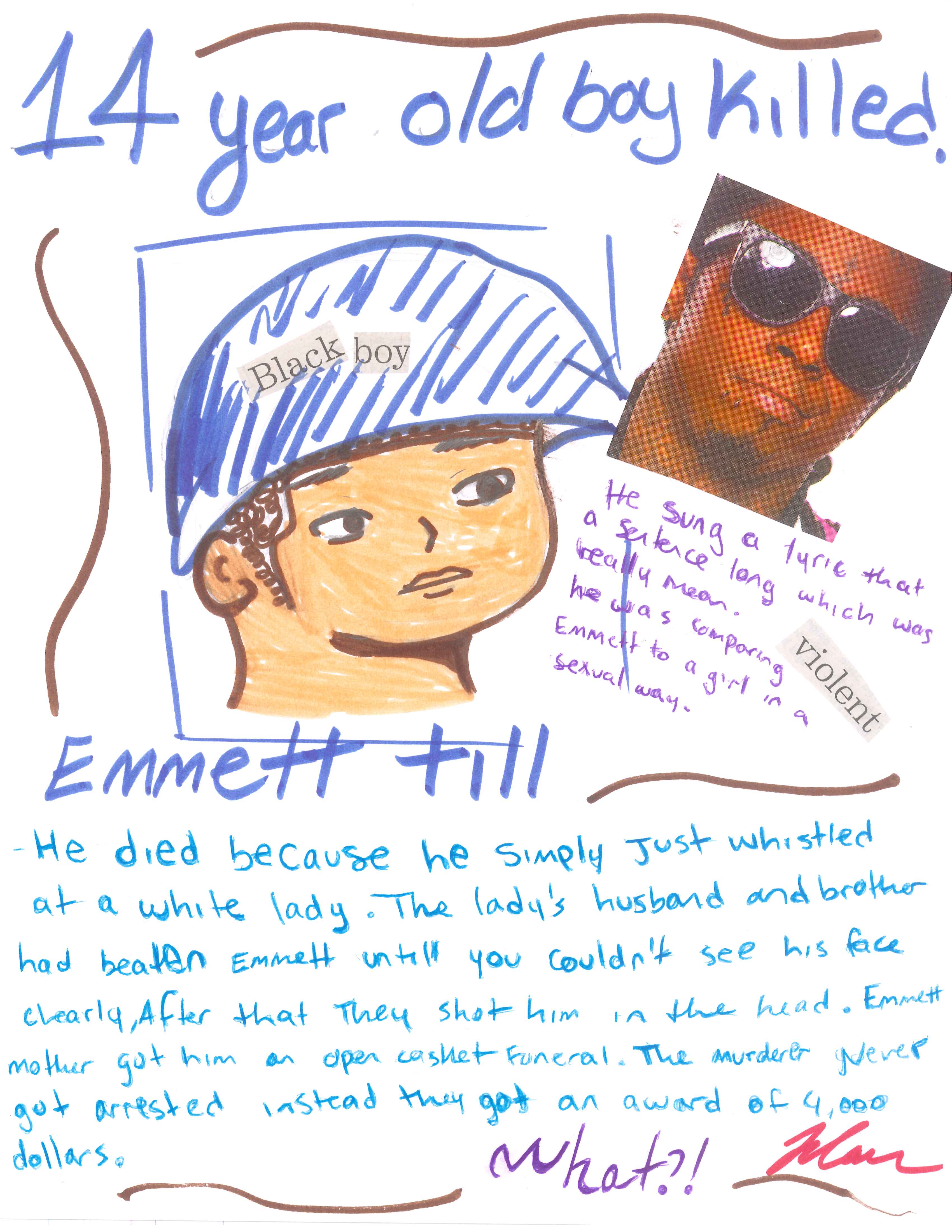

Zine Making

In the summers of 2014 and 2015, we hosted high school students from Philly Futures (now called Heights Philadelphia) to share with them about Du Bois research, including mapping. Maya Beale, a summer intern from Haverford College, led the students in making a zine with their interpretation of how we might interpret Du Bois’ messages today.

In the summers of 2014 and 2015, we hosted high school students from Philly Futures (now called Heights Philadelphia) to share with them about Du Bois research, including mapping. Maya Beale, a summer intern from Haverford College, led the students in making a zine with their interpretation of how we might interpret Du Bois’ messages today.

Unsung Black Women Physicians

For their final course project, then first-year Penn students D’Ayra Johnson and Alyssa Thomas created a podcast called Unsung Black Women Physicians. The students interviewed archivist Margaret Jerido who developed the Black Women’s Physician Project through Drexel University.

“There’s not enough Black people doing research about Black Americans,” Jerido explained, adding that it has become increasingly difficult for Black people to access funding for historical projects.

Ky Core's Curriculum

Ky Core grew up in West Philadelphia and attended Friends Select High School in Center City before enrolling in Mt. Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. They worked as a summer intern on THE WARD during the summer before their senior year of college.

As an English major with a Biology minor with a mission to become a physician assistant, they wanted to develop a project blending storytelling and healthcare. They outlined a curriculum unit focused on how Black communities have faced healthcare crises in the face of racial oppression, emphasizing community organizing and the concept of harm reduction.

The lesson plans they developed allow high school students to engage with the stories of Mercy-Douglass Hospital, which served Black communities between 1895 and 1973, Bebashi, a nonprofit started in 1985 to provide services to low-income people of color living with HIV/AIDS, and the Black Doctor’s Consortium created in 2021 to provide COVID-19 testing and vaccines in Philadelphia’s Black communities.

Curriculum Designed by Teachers

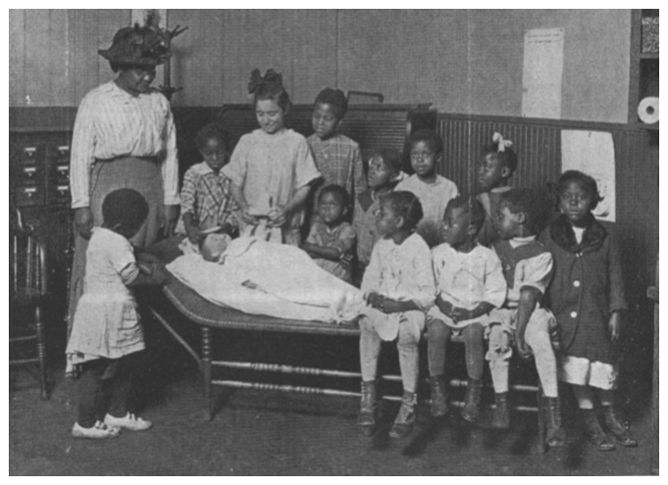

Elizabeth Tyler, pictured at left, provided essential healthcare to Black children and families. Photograph courtesy of Temple University Urban Archives.

Danina Garcia is literary specialist with the School District of Philadelphia. Through the Teachers Institute of Philadelphia (TIP), she developed a curriculum unit focused on Elizabeth Tyler.

Tyler was a Black nurse who worked in New York and Philadelphia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to mitigate racial health disparities in tuberculosis.

The unit “uses primary sources as layered texts to introduce students to the impact of tuberculosis as a disease, the need for treatment in Philadelphia and New York, and the revolutionary impact of Black medical professionals, exemplified in Elizabeth Tyler.

This unit is intended as a counter-narrative and introduction to current District curriculum on *The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks*, but would also work as an introductory unit to any study of infectious diseases or primary source historical research.”

Additional Learning

Explore the other curriculum units developed by TIP teachers.